Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is a geographical term used to describe the area of the African continent which lies south of the Sahara, or those African countries which are fully or partially located south of the Sahara.[1][2] It contrasts with North Africa, which is considered a part of the Arab world.[3][4][5][6][7]

The Sahel is the transitional zone between the Sahara and the tropical savanna (the Sudan region) and forest-savanna mosaic to the south. The Horn of Africa and large areas of Sudan are geographically part of Sub-Saharan Africa, but also part of the Arab world.[3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10]

The Sub-Saharan region is also known as Black Africa,[11] in reference to its many black populations. Commentators in Arabic in the medieval period used a similar term, bilâd as-sûdân, for the region south of the Sahara, which literally translates as "land of the blacks."[12]

According to scientific studies natural human skin colour diversity is highest in black or Sub-Saharan African populations.[13]

Since probably the 5.9 kiloyear event,[14][15] the Saharan and Sub-Saharan regions of Africa have been separated by the extremely harsh climate of the sparsely populated Sahara, forming an effective barrier interrupted by only the Nile River in Sudan, though the Nile was blocked by the river's cataracts. The Sahara Pump Theory explains how flora and fauna (including Homo sapiens) left Africa to penetrate the Middle East and beyond to Europe and Asia. African pluvial periods are associated with a "wet Sahara" phase during which larger lakes and more rivers exist.[16]

Contents |

Climate zones and ecoregions

Sub-Saharan Africa has a wide variety of climate zones or biomes. South Africa and the Democratic Republic of the Congo in particular are considered Megadiverse countries.

- The Sahel shoots across all of Africa at a latitude of about 10° to 15° N. Countries that include parts of the Sahara proper in their northern territories and parts of the Sahel in their southern region include Mali, Niger, Chad and Sudan.

- South of the Sahel, there is a belt of savanna, (Guinean forest-savanna mosaic, Northern Congolian forest-savanna mosaic) widening to include most of Southern Sudan and Ethiopia in the east (East Sudanian savanna).

- The Horn of Africa includes arid semi-desert along its coast, contrasting with savannah and moist broadleaf forests in the interior of Ethiopia.

- Africa's tropical rainforest stretches along the southern coast of West Africa and dominates Central Africa (the Congo) west of the African Great Lakes

- The Eastern Miombo woodlands are an ecoregion of Tanzania, Malawi, and Mozambique.

- The Serengeti ecosystem is located in north-western Tanzania and extends to south-western Kenya.

- The Kalahari Basin includes the Kalahari Desert surrounded by a belt of semi-desert

- The Bushveld is a tropical savanna ecoregion of Southern Africa.

- The Karoo is a semi-desert in western South Africa.

History

Nubia in present day Sudan and other regions south of Egypt, in Sub-Saharan Africa, was referred to as "Ethiopia" or "Aethiopia" ("land of the burnt face") by the Greeks.[17]

Prehistory

According to paleontology, early hominid skull anatomy was similar to their close cousins, the great African forest apes, gorilla and chimpanzee but they had adopted a bipedal locomotion and freed hands, giving them a crucial advantage, as this enabled them to live in both forested areas and on the open savanna at a time when Africa was drying up, with savanna encroaching on forested areas. This occurred 10 million to 5 million years ago.[18]

By 3 million years ago several australopithecine(southern apes) hominid species had developed throughout southern, eastern and central Africa. They were tool users not makers of tools. They scavenged for meat and were vegetarians.[18]

About 2.3 million BC, the next major evolutionary step occurred approximately, when primitive stone tools were first used to scavenge kills made by other predators, and harvest carrion for their bones and marrow. In hunting, H. habilis was probably not capable of competing with large predators, and was still more prey than hunter, although H. habilis probably did steal eggs from nests, and may have been able to catch small game, and weakened larger prey (cubs and older animals). The tools were classed as Oldowan.[19]

Around 1.8 million years ago Homo ergaster first appeared in the fossil record in Africa. From Homo ergaster, [Homo erectus](upright man) evolved 1.5 million years. Some of the earlier representatives of this species were still fairly small brained and used primitive stone tools, much like H. habilis. The brain later grew in size and H. erectus eventually developed a more complex stone tool technology called the Acheulean. Possibly the first hunters, H. erectus mastered the art of making fire, and were the first hominids to leave Africa, colonizing the entire Old World, and perhaps later giving rise to Homo floresiensis. Although some recent writers suggest that H. georgicus, a H. habilis descendant, was the first and most primitive hominid to ever live outside Africa, many scientists consider H. georgicus to be an early and primitive member of the H. erectus species.[20][21]

The fossil record shows Homo sapiens living in southern and eastern Africa at least 100,000 and possibly 150,000 years ago. Around 50,000 - 60,000 years ago, their expansion out of Africa launched the colonization of our planet by modern human-beings. By 10,000 BC, Homo erectus has spread to all corners of the world Their migration is indicated by linguistic, cultural and (increasingly) computer-analyzed genetic evidence.[19][22][23]

After the Sahara became a desert, it did not present a totally impenetrable barrier for travelers between North and South due to the application of animal husbandry towards carrying water, food, and supplies across the desert. Prior to the introduction of the camel,[24] the use of oxen, mule, and horses for desert crossing was common, and trade routes followed chains of oases that were strung across the desert. The trans-saharan trade was in full motion by 500 BC, with Carthage being a major economic force for its establishment.[25][26][27] It is thought that the camel was first brought to Egypt after the Persian Empire conquered Egypt in 525 BC, although large herds did not become common enough in North Africa for camels to be the pack animal of choice for the trans-saharan trade.[28]

East Africa

The distribution of the Nilo-Saharan linguistic phylum is evidence of a certain coherence of the central Sahara, the Sahel and East Africa in prehistoric times. Much of Ancient Egypt's culture came from Sub-Saharan Africa including her religion, agriculture, and language via the Red Sea Hills.[29] Ancient Nubia appears to have acted as a link connecting Ancient Egypt to Sub-Saharan Africa, based on traces of prehistoric south-to-north gene flow.[30] Kush, Nubia at her greatest phase is considered Sub-Saharan Africa's oldest urban civilization. Nubia was a major source of gold for the ancient world. Nubians built famous structures like the Deffufa, mud brick temples similar to the ziggurats of Mesopotamia in material and function.[31] They built numerous pyramids. Sudan, the site of ancient Nubia, has more pyramids than anywhere in the world.[32]

The Axumite Empire spanned the southern Sahara and the Sahel along the western shore of the Red Sea. Located in northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, Aksum was deeply involved in the trade network between India and the Mediterranean. Emerging from ca. the 4th century BC, it rose to prominence by the 1st century AD. It was succeeded by the Zagwe dynasty in the 10th century. Aksumites carved, constructed monolithic stelaes to cover the graves of their kings like King Ezana's Stele and churches out of pure rock, like Church of St. George at Lalibela.

In Ancient Somalia, city-states such as Opone, Mosyllon and Malao that competed with the Sabaeans, Parthians and Axumites for the wealthy Indo-Greco-Roman trade flourished in Somalia.[33]

In the Middle Ages, several powerful Somali empires dominated the regional trade including the Ajuuraan State, which excelled in hydraulic engineering and fortress building,[34] the Sultanate of Adal, whose general Ahmed Gurey was the first African commander in history to use cannon warfare on the continent during Adal's conquest of the Ethiopian Empire,[35] and the Gobroon Dynasty, whose military dominance forced governors of the Omani empire north of the city of Lamu to pay tribute to the Somali Sultan Ahmed Yusuf.[36] In the late 19th century after the Berlin conference had ended, European empires sailed with their armies to the Horn of Africa. The imperial clouds wavering over Somalia alarmed the Dervish leader Muhammad Abdullah Hassan, who gathered Somali soldiers from across the Horn of Africa and began one of the longest colonial resistance wars ever.

Further south in East Africa, during the first millennium AD, Nilotic and Bantu-speaking peoples moved into the region, and the latter now comprise three-quarters of Kenya's population. Increased trade (namely with Arab merchants) and the development of ports saw the birth of Swahili culture. Developed from an outgrowth of indigenous Bantu settlements[37], the Swahili Coast of Kenya, Tanzania and northern Mozambique was part of the east African region which traded with Persia, China, the Arab world, and India especially for ivory and slaves.

In 1498, Vasco da Gama became the first European to reach the East African coast, and by 1525 the Portuguese had subdued the entire coast. Portuguese control lasted until the early 18th century, when Arabs from Oman established a foothold in the region. Assisted by Omani Arabs, the indigenous coastal dwellers succeeded in driving the Portuguese from the area north of the Ruvuma River by the early 18th century.

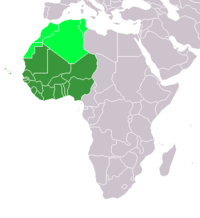

West Africa

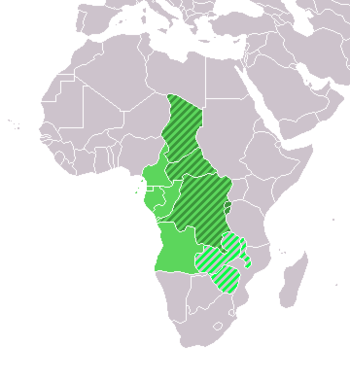

The Bantu expansion is a major migration movement originating in West Africa around 2500 BC, reaching East and Central Africa by 1000 BC and Southern Africa by the early centuries AD.

The Nok culture is known from a type of terracotta figure found in Nigeria, dating to between 500 BC and AD 200.

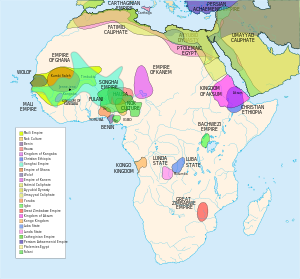

There were a number of medieval empires of the southern Sahara and the Sahel, based on trans-Saharan trade, including the Ghana Empire and the Mali Empire, Songhai Empire, the Kanem Empire and the subsequent Bornu Empire.[38] They built stone structures like in Tichit, but mainly built in mud, adobe. The Great Mosque of Djenne is most reflective of Sahelian Architecture and is the largest adobe building in the world.

In the forest zone, several states and empires emerge. The Ashante Empire arose in the 16th century, in modern day Ghana and Ivory Coast. The oldest kingdom in Nigeria, the Kingdom of Nri, was established by the Igbo in the 11th century. Nri was famous for having a priest-king who wielded no military power. Nri was a rare African state as it never dealt in the trade of slaves. All slaves and outcasts that wondered into their territory were freed. Other major states included, the kingdoms of Ifẹ and Oyo in the western block of Nigeria became prominent about 700–900 and 1400 respectively, and center of Yoruba culture. The Yoruba's built massive mud walls around their cities, the most famous Sungbo's Eredo, the largest man made structure in all of Africa. Another prominent kingdom in south western Nigeria was the Kingdom of Benin(1440–1897), whose power lasted between the 15th and 19th century. Their dominance reached as far as the well known city of Eko which was named Lagos by the Portuguese traders and other early European settlers. The Edo speaking people of Benin are known for the Walls of Benin, which is the largest man-made structure in the world.

In the 18th century, the Oyo and the Aro confederacy were responsible for most of the slaves exported from Nigeria, with Britain shipping 2/5 of the slave and France and Portugal 2/3 of all slaves.[41] Following the Napoleonic wars, the British expanded trade with the Nigerian interior. In 1885, British claims to a West African sphere of influence received international recognition and in the following year the Royal Niger Company was chartered under the leadership of Sir George Taubman Goldie. In 1900, the company's territory came under the control of the British Government, which moved to consolidate its hold over the area of modern Nigeria. On January 1, 1901, Nigeria became a British protectorate, part of the British Empire, the foremost world power at the time.

By 1960, most of the region received independence from colonial rule.

Central Africa

At Urewe, in the first half of the 1st millennium BC. There follow a series of southwards advances, establishing a Congo nucleus by the end of the 1st millennium BC. In a final movement, the Bantu expansion reaches Southern Africa in the 1st millennium AD.

During the 1300, the Luba Kingdom in Southeast Congo near Lake Kisale came about under a king, whose political authority came from religious spiritual legitimacy and is seen as a spiritual guardian. The kingdom controlled agriculture and trade in the region of salt and iron from the north, copper from the Zambian/Congo copper belt.[42]

Rival kingship factions who split from the Luba Kingdom later moved among the Lunda people, marrying into its elite and laying the foundation of the Lunda Empire in the 16th century. The ruling dynasty centralised authority among the Lunda, under the Mwata Yamyo or Mwaant Yaav. The Mwata Yamyo's legitimacy, like the Luba king, came from being viewed as a spiritual religious guardian. This system of religious spiritual kings was spread to most of central Africa by rivals in kingship migrating and forming new states. Many new states kings received legitimacy by claiming descent from the Lunda dynasties.[42]

Another significant kingdom in west central Africa was the Kingdom of Kongo, which existed from the Atlantic west to the Kwango river to the east. During the 15th century, the Bakongo farming community was united with the capital at Mbanza Kongo, under the king title , Manikongo.[42]

Other significant states and peoples included the Kuba Kingdom, producers of the famous raffia cloth, the Eastern Lunda, Bemba, Burundi, Rwanda, and the Kingdom of Ndongo.

Southern Africa

Settlements of Bantu-speaking peoples, who were iron-using agriculturists and herdsmen, were already present south of the Limpopo River by the 4th or 5th century (see Bantu expansion) displacing and absorbing the original Khoi-San speakers. They slowly moved south and the earliest ironworks in modern-day KwaZulu-Natal Province are believed to date from around 1050. The southernmost group was the Xhosa people, whose language incorporates certain linguistic traits from the earlier Khoi-San people, reaching the Fish River, in today's Eastern Cape Province.

Monomotapa was a medieval kingdom (c. 1250–1629) which used to stretch between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers of Southern Africa in the modern states of Zimbabwe and Mozambique. It enjoys great fame for the ruins at its old capital of Great Zimbabwe.

In 1487, Bartolomeu Dias became the first European to reach the southernmost tip of Africa. In 1652, a victualling station was established at the Cape of Good Hope by Jan van Riebeeck on behalf of the Dutch East India Company. For most of the 17th and 18th centuries, the slowly-expanding settlement was a Dutch possession.

Great Britain seized the Cape of Good Hope area in 1795, ostensibly to stop it falling into the hands of the French but also seeking to use Cape Town in particular as a stop on the route to Australia and India. It was later returned to the Dutch in 1803, but soon afterwards the Dutch East India Company declared bankruptcy, and the British annexed the Cape Colony in 1806.

The Zulu Kingdom (1817–79) was a Southern African tribal state in what is now Kwa-Zulu Natal in south-eastern South Africa. The small kingdom gained world fame during and after the Anglo-Zulu War.

During the 1950s and early 1960s, most Sub-Saharan African nations achieved independence from imperialist rule.[43]

Demographics

Sub-Saharan Africa is the poorest region in the world, suffering from the effects of economic mismanagement, corruption in local government, and inter-ethnic conflict. The region contains most of the least developed countries in the world. The Sub-Saharan African countries form the bulk of the ACP countries. Malaria is a chronic impediment to economic development. The disease slows growth by about 1.3% per year through lost time due to illness and the cost of treatment and prevention measures. According to the World Bank, the region's GDP would have been 32% higher in 2003 had the disease been eradicated in 1960.[44]

The population of Sub-Saharan Africa was 800 million in 2007.[45] The current growth rate is 2.3%. The UN predicts for the region a population of nearly 1.5 billion in 2050.[46]

Sub-Saharan African countries top the list of countries and territories by fertility rate with 40 of the highest 50, all with TFR greater than 4 in 2008. All are above the world average except South Africa. Figures for life expectancy, malnourishment, infant mortality and HIV/AIDS infections are also dramatic. More than 40% of the population in sub-Saharan countries is younger than 15 years old, as well as in the Sudan with the exception of South Africa.[47]

Sub-Saharan Africa has a very high child mortality rate. While in 2002, one in six (17%) children died before the age of five,[48] by 2007 this rate had declined to one in seven (15%).[49] The leading cause of death was malaria infection.[44]

Besides bad news in Zimbabwe, Congo, Sudan, and Kenya, most African governments have become more transparent and democratic. Most African governments were elected by the people and enjoys the support of the populace. Last year 54 million Africans voted in 19 peaceful presidential and parliamentary elections.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) in Africa has grown at an average of 146 per cent a year over the last 22 years to reach US$36 billion in 2007, while trade between Africa and the rest of the world particularly Asia has been steadily increasing. Most notable, bilateral trade between China and Africa jumped 45 per cent in 2008 to reach US$107 billion, the bulk of which went to Sub-Saharan Africa.

Real economic growth in 2 out of 5 Sub-Saharan countries was triple that of the US economy last year, on a pace that rivals that of Southeast Asia in 1980. African economies from Senegal to Benin to the Democratic Republic of Congo are more diversified. Growth in the region is expected to hit 6.5 percent.[50]

Sub-Saharan Africa’s economy would probably expand 1.3 percent in 2009, down from 5.5 percent in 2008, and compared with a forecast of 1.5 percent made by the IMF in July. Growth will rebound to 4.1 percent in 2010 as global trade improves.[51]

| Country | Population | Area | Literacy(M/F)[52] | GDP per Captia[52] | Trans( Rank/Score)[53] | Life(Exp.)[52] | HDI | EODBR/SAB [54] | PFI(RANK/MARK) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12,799,293 | 1,246,700 | NA | 1070 | 162/1.9 | 42.4 | 0.564 | 169/165 | 119/36,50 | |

| 8,988,091 | 27,830 | 67.3%/52.2% | 101 | 168/1.8 | 49 | 0.394 | 176/130 | 103/29,00 | |

| 68,692,542 | 2,345,410 | 80.9%/54.1% | 91 | 162/11.9 | 46.1 | 0.389 | 182/152 | 146/53,50 | |

| 10,473,282 | 26,338 | 71.4%/59.8% | 263 | 89/3.3 | 46.8 | 0.460 | 67/11 | 157/64,67 | |

| 212,679 | 1,001 | 92.2%/77.9% | N/A | 111/2.8 | 65.2 | 0.651 | 180/140 | NA | |

| 18,879,301 | 475,440 | 77%/59.8% | 687 | 146/2.2 | 50.3 | 0.523 | 171/174 | 109/30,50 | |

| 4,511,488 | 622,984 | 64.8%/33.5% | 22 | 158/2.8 | 44.4 | 0.369 | 183/159 | 80/17,75 | |

| 10,329,208 | 1,284,000 | 40.8%/12.8% | 266 | 175/1.6 | 50.6 | 0.392 | 178/182 | 132/44,50 | |

| 3,700,000 | 342,000 | 90.5%/ 79.0% | 1,145 | 162/1.9 | 54.8 | 0.755 | N/A | 116/34,25 | |

| 633,441 | 28,051 | 93.4%/80.3% | 7,470 | 168/1.8 | 51.1 | 0.719 | 170/178 | 158/65,50 | |

| 1,514,993 | 267,667 | 88.5%/79.7% | 4,263 | 106/2.9 | 56.7 | 0.755 | 158/152 | 129/43,50 | |

| 39,002,772 | 582,650 | 77.7%/70.2 | 440 | 146/2.2 | 53.4 | 0.541 | 95/124 | 96/25,00 | |

| 41,048,532 | 945,087 | 77.5%/62.2% | 339 | 126/2.6 | 51.9 | 0.530 | 131/120 | NA/15,50 | |

| 32,369,558 | 236,040 | 76.8%/57.7 | 274 | 130/2.5 | 50.7 | 0.514 | 112/129 | 86/21,50 | |

| 41,087,825 | 2,505,810 | 71.1%/51.8% | 489 | 176/1.5 | 58.1 | 0.531 | 154/118 | 148/54,00 | |

| 516,055 | 23,000 | N/A | 817 | 111/2.8 | 54.5 | 0.520 | 163/177 | 110/31,00 | |

| 5,647,168 | 121,320 | N/A | 160 | 126/2.6 | 57.3 | 0.472 | 175/181 | 175/115,50 | |

| 85,237,338 | 1,127,127 | 50%/28.8% | 161 | 120/2.7 | 52.5 | 0.414 | 107/93 | 140/49,00 | |

| 9,832,017 | 637,657 | N/A | N/A | 180/1.1 | 47.7 | 0.284 | N/A | 164/77,50 | |

| 1,990,876 | 600,370 | 80.4%/81.8% | 4,511 | 37/5.6 | 49.8 | 0.694 | 45/83 | 62/15,50 | |

| 752,438 | 2,170 | N/A | 382 | 143/2.3 | 63.2 | 0.576 | 162/168 | 82/19,00 | |

| 2,130,819 | 30,355 | 73.7%/90.3% | 528 | 89/3.3 | 42.9 | 0.514 | 130/131 | 99/27,50 | |

| 19,625,000 | 587,041 | 76.5%/65.3% | 238 | 99/3.0 | 59 | 0.543 | 134/12 | 134/45,83 | |

| 14,268,711 | 118,480 | N/A | 145 | 89/3.3 | 47.6 | 0.493 | 132/128 | 62/15,50 | |

| 1,284,264 | 2,040 | 88.2%/80.5% | 4,522 | 42/5.4 | 73.2 | 0.804 | 17/10 | 51/14,00 | |

| 21,669,278 | 801,590 | N/A | 330 | 130/2.5 | 42.5 | 0.402 | 135/96 | 82/19,00 | |

| 2,108,665 | 825,418 | 86.8%/83.6% | 2166 | 56/4.5 | 52.5 | 0.686 | 66/123 | 35/9,00 | |

| 87,476 | 455 | 91.4%/92.3% | 7,005 | 54/4.8 | 72.2 | 0.845 | 111/81 | 72/16,00 | |

| 49,052,489 | 1,219,912 | N/A | 3,562 | 55/4.7 | 50.7 | 0.683 | 34/67 | 33/8,50 | |

| 1,123,913 | 17,363 | 80.9%/78.3% | 1,297 | 79/3.6 | 40.8 | 0.572 | 115/158 | 144/52,50 | |

| 11,862,740 | 752,614 | N/A | 371 | 99/3.0 | 41.7 | 0.481 | 90/94 | 97/26,75 | |

| 11,392,629 | 390,580 | 92.7%/86.2% | N/A | 146/2.2 | 42.7 | 0.513 | 159/155 | 136/46,50 | |

| 8,791,832 | 112,620 | 47.9%/42.3% | 323 | 106/2.9 | 56.2 | 0.492 | 172/155 | 97/26,75 | |

| 12,666,987 | 1,240,000 | 32.7%/15.9% | 290 | 111/2.8 | 53.8 | 0.371 | 156/139 | 38/8,00 |

GDP Per Capital (2006 in dollars($)), Life(Exp.) (Life Expectancy 2006), Literacy(Male/Female 2006), Trans (Transparency 2009), HDI (Human Development Index), EODBR (Ease of Doing Business Rank June 2008 through May 2009), SAB (Starting a Business June 2008 through May 2009) , PFI (Press Freedom Index 2009)

Economy

Energy and power

50% of Africa is rural, with no access to electricity. Africa generates 47 MW of electricity, less than 0.6% of global market share. Many countries are besieged by power shortages.[55]

Because of rising prices in commodities such as coal and oil, thermal sources of energy are proving to be too expensive for power generation in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sub-Saharan Africa is expected to build additional hydropower generation capacity of at least 20,165 MW by 2014. The region has the potential to generate 1,750 TWh of energy, of which only 7 per cent has been explored. African governments are taking advantage of the readily available hydro resources to broaden their energy mix. Hydro Turbine Markets in Sub-Saharan Africa generated revenues of $120.0 million in 2007 and is estimated to reach $425.0 million. Asian countries, notably China, India and Japan, are playing an active role in power projects across the African continent. The majority of these power projects are hydro-based because of China's vast experience in the construction of hydro-power projects and part of the Energy & Power Growth Partnership Services programme.[56][57]

With electrification numbers, Sub-Saharan Africa with access to the Sahara and being in the tropical zones(365 days of sun) has massive potential for solar photovoltaic(PV) electrical potential.[58] 600 million people could be served with electricity based on its PV potential.[59] China is promising to train 10,000 technicians from Africa and other developing countries in the use of solar energy technologies over the next five years. Training African technicians to use solar power is part of the China-Africa science and technology cooperation agreement signed by the Chinese science minister and African counterparts during premier Wen Jiabao's visit to Ethiopia last December.[60]

Media

Radio is the major source of information in Sub-Saharan Africa though that might change.[61]

Cell phone usage in Sub-saharan has brought about a revolution. In Sub-Saharan Africa, average penetration stands at more than a third of the population. Sub-Saharan countries such as Gabon, Seychelles, and South Africa now boast almost 100% penetration. Only five Sub-Saharan African countries—Burundi, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Somalia—still have a penetration of less than 10%. Cellphones are used to transfer money using the SMS feature and searching for best prices for farmer's produce. For example in Niger delivery of the best price information for produce has resulted in lower prices for the consumer and increased profits for traders. Broadband penetration outside of South Africa has been limited and where it is exorbitantly expensive.[62][63] Access to the internet via cell phones is on the rise.[64]

Television is the second major source of information for most Sub-Saharan Africans.[61] Due to power shortages, the spread of television viewing has been limited. 1 in 13 have television in Sub-Saharan Africa, a total of 62 million. But those in the television industry view Sub-Saharan Africa as an untapped green market. Digital television and pay for service are on the rise.[65]

Infrastructure

Less than 40 percent of rural Africans live within two kilometers of an all-season road, the lowest level of rural accessibility in the developing world. Spending on roads in Sub-Saharan Africa averages just below 2 percent of GDP with varying degree among countries. This compares with the 1 percent of GDP that is typical in industrialized countries, and the 2–3 percent of GDP found in fast-growing emerging economies. Although the level of effort is high relative to the size of Africa’s economies, it remains little in absolute terms, with low-income countries spending an average of about US$7 per capita per year.[66]

Oil and minerals

Sub-Saharan Africa is rich in minerals. The region is a major exporter to the world of gold, uranium, chrome, vanadium, antimony, coltan, bauxite, iron ore, copper and manganese. South Africa is a major exporter of manganese.[67] South Africa is also a major supplier of chrome. About 42% of world reserves and about 75% of the world reserve are located in South Africa.[68] In addition, South Africa is the largest producer of platinum. 80% of the total world's annual mine production is from South Africa. 88% of the world's platinum reserve is in South Africa.[69] Sub-saharan Africa produces 33% of the world's bauxite with Guinea as the major supplier.[70] Zambia is a major producer of copper.[71] Democratic Republic of Congo is a major source of coltan. Production from Congo is very small but has 80% of proven reserves.[72] Sub-saharan Africa is a major producer of gold, producing up to 30% of global production. Major suppliers are South Africa, Ghana, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Guinea, and Mali. South Africa had been first in the world in terms of gold production since 1905 but in 2007 it moved to second place, according to GFMS, the precious metals consultancy.[73] Uranium is major commodity from the region. Significant suppliers are Niger, Namibia, and South Africa. Namibia was the number one supplier from Sub-Saharan Africa in 2008.[74]

Sub-Saharan Africa produces 49% of the world's diamonds.

By 2015, it is estimated that 25% of North American oil will be from Sub-Saharan Africa, way ahead of the Middle East. Sub-Saharan Africa has been the focus of an intense race for oil by the West and China, India, and other emerging economies, even having only 10% of proven oil reserves, less than the Middle East. This race has been referred to as the second Scramble for Africa. The reasons are all economic. Most of Sub-Saharan oil is off the coast of host countries. Transportation cost is reduce. No pipelines has to be laid as in Central Asia. No Suez Canals to pass through as in the Middle East. Ships can come load up and hit the ocean to North America, Europe, or Asia. If political turmoil hits host country, production never stops since operation is off-shore. Second, Sub-Saharan oil is viscous and has very low sulfur content. This requires less refining, thereby less costly and within environmental regulations. New sources of oil are being located in Sub-Saharan Africa more frequently than anywhere else. Of all new sources of oil, 1/3 are in Sub-saharan africa.[75]

Agriculture

Agriculture has always been an integral activity in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sub-Saharan Africa has more variety of grains than anywhere in the world. Between 13,000 and 11,000 BCE wild grains began to be collected as a source of food in the cataract region of the nile, south of Egypt. The collecting of wild grains as source of food spread to Syria, parts of Turkey and Iran by the eleventh millennium BCE. By the tenth and ninth millennia southwest Asians domesticated their wild grains, wheat and barley after the notion of collecting wild grains was spread from the Nile.[76]

Numerous crops have been domesticated in the region and spread to world. These crops included sorghum, castor beans, coffee, cotton[77] okra, black-eyed peas, watermelon, gourd, and pearl millet. Other domesticated crops included teff, enset, African rice, yams, kola nuts, oil palm, and raffia palm.[78].[76]

Domesticated animals included the guinea fowl and the donkey.

Agriculture represents 20% to 30% of GDP in Sub-Saharan Africa. Agriculture represents 50% of exports. In some cases, 60% to 90% of the labor force are employed in agriculture.[79]

Most agricultural activity in Sub-Saharan Africa is subsistence farming. This has made agricultural activity vulnerable to climate change and global warming. Biotechnology has been advocated to create high yield, pest and environmentally resistant crops in the hands of small farmers. The Bill and Malinda Gates foundation are strong advocates and donors to this cause. Biotechnology and GM crops have met resistance both by Sub-Saharan Africans and Environmental groups.[80]

Cash crops include cotton, coffee, tea, cocoa, sugar, and tobacco.[81]

The OECD says Africa has the potential to become an agricultural superbloc, if it can unlock the wealth of the savannahs by allowing farmers to use their land as collateral for credit.[82] Recently, there have been a trend to purchase large tracts of land in Sub-Sahara for agricultural use by developing countries. Earlier in 2009, legendary hedge fund speculator George Soros highlighted a new farmland buying frenzy caused by growing population, scarce water supplies and climate change. Chinese interests bought up large swathes of Senegal to supply it with sesame. Aggressive moves by China, South Korea and Gulf states to buy vast tracts of agricultural land in Sub-Saharan Africa could soon be limited by a new global international protocol.[83]

Education

Forty percent of African scientists live in OECD countries, predominantly western countries.[84] This has been described as an African brain drain. Even with the drain, Sub-Saharan Africa generates lots of growth in enrollment in higher education. Enrollments in Sub-Saharan African universities tripled between 1991 and 2005, expanding at an annual rate of 8.7 percent, which is one of the highest regional growth rates in the world. In the last 10 to 15 years increase mobility to pursue university level degrees abroad has increased. In some OECD countries, like the United States, Sub-saharan Africans are the most educated immigrant group.[84]

Sub-Saharan African countries spent an average of just 0.3% of their GDP on S&T(Science and Technology) in 2007. This represent and increase from US$1.8bn in 2002 to US$2.8bn in 2007. This represent an increase of 50% in spending in S&T in Africa. South Africa is the sole exception. South Africa spends 0.87% of GDP on S&T.[85][86]

Health care

In 1987, the Bamako Initiative conference organized by the World Health Organization was held in Bamako, the capital of Mali, and helped reshape the health policy of Sub-Saharan Africa.[87] The new strategy dramatically increased accessibility through community-based healthcare reform, resulting in more efficient and equitable provision of services. A comprehensive approach strategy was extended to all areas of health care, with subsequent improvement in the health care indicators and improvement in health care efficiency and cost.[88][89]

As of October 2006, many governments face difficulties in implementing policies aimed at tackling the effects of the AIDS pandemic due to lack of technical support despite a number of mitigating measures.[90]

Languages and ethnic groups

Sub-Saharan Africa displays more diversity than anywhere in the world. This is more apparent in the number of languages spoken. The region speaks 1000 languages, which is 1/6 of the world's total.[81]

With the exception of extinct Sumerian, the Afro-Asiatic has the longest documented history of any language phyla in the world. Egyptian was recorded as early as 3200 BC. The Semitic branch was record as early as 2500 BC.[91] The distribution of the Afro-Asiatic languages within Africa is principally concentrated in North Africa and Horn of Africa. The Chadic branch is distributed in Central and West Africa.[92]. Hausa is a lingua franca in West Africa(Niger, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Cameroon, and Chad).[93] The Semitic branch of the phylum also has a notable presence in Western Asia, making Afro-Asiatic the only language family spoken in Africa that is also attested outside of the continent. In addition to languages now spoken, Afro-Asiatic includes several ancient languages, such as Ancient Egyptian, Biblical Hebrew and Akkadian. Most linguists place the origin of the Afro-Asiatic at the Horn of Africa, which has a greater variety of sub-families than any other region.

The Khoi-San languages represent the oldest language family in the world.[94] They include languages indigenous to Southern and Eastern Africa, though some, such as the Khoi languages, appear to have moved to their current locations not long before the Bantu expansion.[95] In Southern Africa, their speakers are the Khoi and Bushmen (San), in East Africa, the Sandawe and Hadza.

The Niger-Congo phylum is the largest linguistic family in the world in terms of the number of languages (1436) it contains.[96] The vast majority of languages of this family are tonal such as Yoruba and Igbo. A major branch of Niger-Congo languages is the Bantu family, which covers a greater geographic area than the rest of the family put together. Bantu speakers represent the majority of inhabitants in southern, central and southeastern Africa, though Pygmy, Khoisan (Bushmen), and Nilotic groups, respectively, can also be found in those regions. Bantu-speakers can also be found in parts of West Africa such as the Gabon, Equatorial Guinea and southern Cameroon. Swahili, a Bantu language with many Arabic, Persian and other Middle Eastern and South Asian loan words, developed as a lingua franca for trade between the different peoples. In the Kalahari Desert of Southern Africa, the distinct people known as the Bushmen (also "San", closely related to, but distinct from "Hottentots") have long been present. The San evince unique physical traits, and are the indigenous people of southern Africa. Pygmies are the pre-Bantu indigenous peoples of central Africa.

The Nilo-Saharan languages are concentrated in the upper parts of the Chari and Nile rivers. They are principally spoken by Nilotic ethnic groups. The Old Nubian language is also a member of this phylum.

South Africa has the largest populations of Whites, Indians and Coloureds in Africa. The term "Coloured" is used to describe persons of mixed race in South Africa and Namibia. People of European descent in South Africa include the Afrikaner and a sizeable populations of Anglo-Africans and Portuguese Africans. Madagascar's population is predominantly of mixed Austronesian (Pacific Islander) and African origin. The area of southern Sudan is inhabited by Nilotic people.

The notion of a tribal Sub-Saharan Africa is widespread. This notion was perpetuated during the colonial period. Tribal meant that Africans lived in small homogenous communities and isolated from the rest of the world. Bonds were based on basic kinship and affinity. Government institution were unsophisticated. This notion could be applied to Central Africa with its dense Forest. But were the people "tribal?" This is far from the case. The Kuba built sophisticated political systems that could initiate cultural change. Its political institutions altered patterns of marriage and increased agricultural productivity. Via the river system in the dense jungles, they were involve in a wide intra-regional network of trade.[97] All of Africa was connected via trade. West Africa was trading with Great Zimbabwe. Great Zimbabwe was trading with Asia, via the Swahilis with China. Trade routes existed, going through Central Africa from the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic Ocean. European explorers, during the 19th century made use of these trade routes with assistance from African middlemen.[98]

The term "tribe", "tribal" present a value judgement. During the late 1960s the Igbos, a population of 10 million, were referred to as a tribe during the Nigerian civil war. Ruthenians an ethnique of less than 200,000(who reside in Slovakia, Poland, and Belorus) and fewer than 400,000 citizens of Malta are referred to as nationalities.[99] Sub-saharan art is referred to as "tribal" "primitive" art but makes use of fractals or non-linear scaling.[100] Fractal geometry was discovered in the latter part of the 20th century.

List of major languages of Sub-Saharan Africa by region, family and total number of native speakers in millions:

- East Africa

- Niger-Congo, Narrow Bantu:

- Swahili: 5-10

- Chichewa: 9

- Gikuyu (Kenya): 5

- Luhya: 4

- Nilo-Saharan

- Luo

- Shilluk

- West Africa

- Niger-Congo

- Afro-Asiatic

- Hausa: 24

- Nilo-Saharan

- Kanuri: 4

- Southern Africa

- Niger-Congo, Narrow Bantu

- Central Africa

- Niger-Congo, Narrow Bantu

- Kinyarwanda (Rwanda) 7

- Kongo: 7

- Tshiluba: 6

- Kirundi: 5

Religion

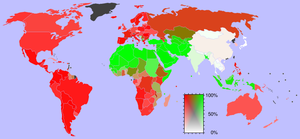

In terms of religion, Sub-Saharan Africa — with the exception of the predominantly Muslim Horn of Africa,[101] Sudan,[103] the Swahili coast,[104] and the Sahel[105] — is mostly Christian or home to many traditional African religions.[106][107]

Traditional African religions can be broken into down linguistic cultural groups, with common themes. Among Niger-Congo-speakers is a belief in a creator God; ancestor spirits; territorial spirits; evil caused by human ill will and neglecting ancestor spirits; priest of territorial spirits. New world religions such as Santería, Vodun, and Candomblé, would be derived from this world view. Among Nilo-Saharan speakers, is the belief in Divinity; evil is caused by divine judgement and retribution; prophets as middlemen between Divinity and man. Among Afro-Asiatic-speakers is henotheism, the belief in one's own gods but accepting the existence of other gods; evil here is caused by malevolent spirits. The Semitic Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam would have originated from the latter world view.[108] Khoisan religion is non-theistic but a belief in a Spirit or Power of existence which can be tapped in a trance-dance; trance-healers.[109]

Traditional Sub-Saharan African religion displays very complex ontology, cosmology, and metaphysics. Mythologies, for example, demonstrated the difficulty fathers of creation had in bringing about order from chaos. Order is what is right and natural and any deviation is chaos. Sub-Saharan cosmology and ontology is neither simple or linear. It defines duality, the material and immaterial, male and female, heaven and earth. Common principles of being and becoming are widespread: Among the Dogon, the principle of Amma(being) and Nummo(becoming), among the Bambara Pemba(being) and Faro(becoming),[110]

- West Africa

- Akan mythology

- Ashanti mythology (Ghana)

- Dahomey (Fon) mythology

- Efik mythology (Nigeria, Cameroon)

- Igbo mythology (Nigeria, Cameroon)

- Isoko mythology (Nigeria)

- Yoruba mythology (Nigeria, Benin)

- Central Africa

- Bushongo mythology (Congo)

- Bambuti (Pygmy) mythology (Congo)

- Lugbara mythology (Congo)

- East Africa

- Akamba mythology (East Kenya)

- Dinka mythology (Sudan)

- Lotuko mythology (Sudan)

- Masai mythology (Kenya, Tanzania)

- Southern Africa

- Khoikhoi mythology

- Lozi mythology (Zambia)

- Tumbuka mythology (Malawi)

- Zulu mythology (South Africa)

Sub-Saharan traditional divination systems displays great sophistication. For example the bamana sand divinition uses well establish symbolic codes that can be reproduce using four bits or marks. A binary system of one or two marks are combined. Random outcomes are generated using a fractal recursive process. It is analogous to a digital circuit, but can be reproduced on any surface with one or two marks. This system is widespread in Sub-Saharan Africa.[111]

Music

Traditional Sub-Saharan African music is as diverse as the region's various populations. The common perception of Sub-Saharan African music is that it is rhythmic music centered around the drums. It is partially true. A large part of Sub-Saharan music, mainly among Niger-Congo linguistic groups is rhythmic and centered around the drum. Sub-Saharan music is polyrhythmic, usually consisting of multiple rhythms in one composition. Dance involves moving multiple body parts. These aspect of Sub-Saharan music has been transferred to the new world by enslaved Sub-Saharan Africans and can be seen in its influence on music forms as Samba, Jazz, Rhythm and Blues, Rock & Roll, Salsa, and Rap music.[81]

But Sub-Saharan music involves a lot of music with strings, horns, and very little poly-rhythms. Music from the eastern sahel and along the nile, among the Nilo-Saharan, made extensive use of strings and horns in ancient times. Among the Afro-Asiatics, we see extensive use of string instruments. Dancing involve swaying body movements and footwork. Among the Khoisans extensive use of string instruments with emphasis on footwork.[112]

Modern Sub-Saharan African music has been influence by music from the New World (Jazz, Salsa, Rhythm and Blues etc.) vice-versa being influenced by enslaved Sub-Saharan Africans. Popular styles are Mbalax in Senegal and Gambia, Highlife in Ghana, Zoblazo in Ivory Coast, Makossa in Cameroon, Soukous in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kizomba in Angola, and Mbaqanga in South Africa. New World styles like Salsa, R&B/Rap, Reggae, and Zouk also have widespread popularity.

Art

The oldest abstract art in the world is a shell necklace dated 82,000 years in the Cave of Pigeons in Taforalt, eastern Morocco.[113] The second oldest abstract form of art and the oldest rock art is found in the Blombos Cave at the Cape in South Africa, dated 77,000 years.[114] The Blombos Cave represent what is man's earliest art form. Sub-saharan Africa has some of the oldest and most varied style of rock art in the world.[115]

Although Sub-saharan African art is very diverse there are some common themes. One is the use of the human figure. Second, there is a preference for sculpture. Sub-saharan art is meant to be experience three dimensionly, not two dimensionly. A house is meant to be experience from all angles. Third, art is meant to be performed. Sub-saharan Africans have specific name for mask. The name incorporates the sculpture, the dance, and the spirit that incorporates the mask. The name denotes all three elements. Fourth, art that serves a practical function, utilitarian. The artist and craftsman are not separate. A sculpture shaped like a hand can be used as a stool. Fifth, the use of fractals or non-linear scaling. The shape of the whole is the shape of the parts at different scales. Before the discovery of fractal geometry, Louis Senghor, Senegal’s first president, referred to this as “dynamic symmetry.” William Fagg, the British art historian, compared it to the logarithmic mapping of natural growth by biologist D’Arcy Thompson. Lastly, Sub-saharan art is visually abstract, instead of naturalistic. Sub-saharan art represents spiritual notions, social norms, ideas, values, etc. An artist might exaggerated the head of a sculpture in relations to the body not because he does not know anatomy but because he wants to illustrate that the head is the seat of knowledge and wisdom. The visual abstraction of African art was very influential in the works of modernist artist like Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Jacques Lipchitz.[116][117]

Cuisine

Sub-Saharan African cuisine like everything about Africa is very diverse. A lot of regional overlapping occurs, but there are dominant elements region by region.

West African cuisine can be described as starchy, flavorfully spicey. Dishes include fufu, kenkey, couscous, garri, foutou, and banku. Ingredients are of native starchy tubers, yams, cocoyams, and cassava. Grains include millet, sorghum, and rice, usually in the sahel, are incorporated. Oils include palm oil and shea butter(sahel). One finds recipes that mixes fish and meat. Beverages are palm wine( sweet or sour) and millet beer. Roasting, baking, boiling, frying, mashing, and spicing are all cooking techniques.

East African cuisine reflects its islamic, geographical Indian Ocean cultural links. Dishes include ugali, injera, wat, sukumi wiki, and halva. Spices such as curry, saffron, cloves, cinnamon, pomegranate juice, cardamon, ghee, and sage are used, especially among Muslims. Meat includes cattle, sheep, and goats, but is rarily eaten since its viewed as currency and wealth.

In the Horn of Africa, pork and non-fish seafood is avoided by Christians and Muslims. Dairy products and all meats are avoided during lent by Ethiopians. Maize(corn) is a major staple from Sudan to southern Africa. Cornmeal is used to make ugali, a popular dish with different names from Sudan to southern Africa. Teff is used to make injera or canjeero(Somali) bread. Other important foods include enset, noog, lentils, rice, banana, leafy greens, chiles, peppers, cocconut milk and tomatoes. Beverages are coffee(domesticated in Ethiopia), chai tea, fermented beer from banana or millet. Cooking techniques include roasting and marinating.

Central African cuisine connects with all major regions of Sub-Saharan Africa: Its cuisine reflects that. Ugali and fufu are eaten in the region. Its cuisine is very starchy and spicy hot. Dominant crops include plantains, cassava, peanuts, chillis, and okra. Meats include beef, chicken, and sometimes exotic meats called bush meat (antelope, warthog, crocodile). Widespread spicy hot fish cuisine is one of the differentiating aspects. Mushroom is sometimes used as a meat substitute.

Traditional Southern African cuisine surrounds meat. Traditional society typically focused on raising, sheep, goats, and especially cattle. Dishes include braai (barbecue meat),sadza, bogobe, pap (fermented cornmeal), milk products (buttermilk, yoghurt). Crops utilized are sorghum, maize (corn), pumpkin beans, leafy greens, and cabbage. Beverages include ting (fermented sorghum or maize), milk, chibuku (milky beer). Influences from the Indian and Malay community can be seen its use of curries, sambals, pickled fish, fish stews, chutney, and samosa. European influences can be seen in cuisines like biltong (dried beef strips), potjies(stews of maize, onions, tomatoes), French wines, and crueler or koeksister (sugar syrup cookie).

Clothing

Like most of the world, Sub-Saharan Africans have adopted Western-style clothing. In some country like Zambia, used Western clothing have flooded markets, causing great angst in the retail community. Sub-Saharan Africa boasts its own traditional clothing style. Cotton seems to be the dominant material. It was domesticated in Nubia and spread.[77]

In East Africa, one finds extensive use cotton clothing. Shemma, shama, and kuta are types of Ethiopian clothing. Kanga are Swahili cloth that comes in rectangular shapes, made of pure cotton, and put together to make clothing. Kitenges are similar to kangas and kikoy, but are of a thicker cloth, and have an edging only on a long side. Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, and Sudan are some of the African countries where kitenge is worn. In Malawi, Namibia and Zambia, kitenge is known as Chitenge. One of the unique materials, which is not a fiber and is used to make clothing is barkcloth, an innovation of the baganda people of Uganda. It came from the Mutuba tree (Ficus natalensis).[118] On Madagascar a type of cloth called Lamba Mpanjaka, made out of silk, was worn like a toga.

In West Africa, again cotton is the material of choice. In the Sahel mainly and other parts of West Africa we have the boubou(male) and kaftan(female) style of clothing. Kente cloth created by the Akan people of Ghana and Ivory Coast, from silk of the various moth species in West Africa. Kente comes from the Ashanti twi word kenten which means basket. It is sometimes used to make dashiki and kufi. Adire is a type of Yoruba cloth that is starch resistant. Raffia cloth and barkcloth are also utilized in the region.

In Central Africa, the Kuba people developed raffia cloth from the raffia plant fibers. It was widely used in the region. Barkcloth was also extensively used.

In Southern Africa one finds numerous use of animal hide and skins for clothing. The Ndau in central Mozambique and the Shona mixed hide with barkcloth, cotton cloth. Cotton cloth was referred to as machira. Xhosa, Tswana, Sotho, and Swazi also made extensive use of hides. Hides came from cattle, sheep, goat, and elephant. Leopard skins were coveted and was a symbol of kingship in Zulu society. Skins were tanned to form leather, dyed, and embedded with beads.

Sports

Football(soccer) is the number one sport in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sub-Saharan men are its main patrons. Major leagues are the African Champions League, a gathering of various football clubs. Africa Cup of Nations is a gathering of 16 teams from various African nations held every two years(January 20 - February 10, 2008). The Confederation Cup is a competition for the National Cup winner in each African country. Finals are in November. Cameroon will play in the World Cup for the sixth time, a record for a Sub-saharan team. South Africa will be host to the 2010 Fifa World Cup, a first for a Sub-Saharan country. In 1996 Nigeria won the gold for football, a momentous achievement for Sub-Saharan African football. Famous Sub-saharan football stars are Emmanuel Adebayor, Obafemi Martins, Michael Essien, Didier Drogba, Jay-Jay Okocha, and Samuel Eto'o Fils. Most talented Sub-saharan Africans find themselves courted and sought after in European leagues. There are currently more than 1000 Africans playing for European clubs. Sub-Saharan Africans have found themselves the target of racism by European fans. Fifa has been trying hard to crack down on racist outburst during games.[119][120][121]

Rugby is also popular in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Confederation of African Rugby governs rugby games in Sub-Saharan Africa and chooses the best team to play in the Rugby World Cup. South Africa is a major force in the game and won the last championship in 2007.

Cricket has a following. The African Cricket Association is an international body which oversees cricket in African countries. South Africa and Zimbabwe has its own governing body. In 2003 the Cricket World Cup was held in South Africa, first time it was held in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Over the years, Ethiopia and Kenya have produced many notable long-distance athletes. Each country has federations that identifies and cultivates top talent. Athletes from Ethiopia and Kenya hold all the distance records (except the 1500 metres) from 800m to the marathon.[122] Famous runners are Haile Gebrselassie, Kenenisa Bekele, Paul Tergat, and John Cheruiyot Korir.[123]

List of countries and regional organization

Only six African countries are not geographically a part of Sub-Saharan Africa: Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia, Western Sahara (claimed by Morocco). Together with the Sudan, they form the UN subregion of Northern Africa. Most international organizations include Sudan as part of sub-Saharan africa. It has a majority Black population in the west(Darfur), south(Dinka, Nuer, etc.) and north (Nubian).[124][125][126][127][128][129][130] Mauritania and Niger only include a band of the Sahel along their southern borders. All other African countries have at least significant portions of their territory within Sub-Saharan Africa.

West Africa

Mauritania cap. Nouakchott cur. Mauritanian ouguiya(UM)

Mauritania cap. Nouakchott cur. Mauritanian ouguiya(UM)

Gambia cap. Banjul cur. Gambian dalasi(D)

Gambia cap. Banjul cur. Gambian dalasi(D) Ghana cap. Accra cur. Ghanaian cedi(GH₵)

Ghana cap. Accra cur. Ghanaian cedi(GH₵) Guinea cap. Conakry cur. Guinean franc(FG)

Guinea cap. Conakry cur. Guinean franc(FG) Liberia cap. Monrovia cur. Liberian dollar(L$)

Liberia cap. Monrovia cur. Liberian dollar(L$) Nigeria cap. Abuja cur. Nigerian naira(N)

Nigeria cap. Abuja cur. Nigerian naira(N) Sierra Leone cap. Freetown cur. Sierra Leonean leone(Le)

Sierra Leone cap. Freetown cur. Sierra Leonean leone(Le)

Benin cap. Porto-Novo cur. West African CFA franc(CFA)

Benin cap. Porto-Novo cur. West African CFA franc(CFA) Burkina Faso cap. Ouagadougou cur. West African CFA franc(CFA)

Burkina Faso cap. Ouagadougou cur. West African CFA franc(CFA) Côte d'Ivoire cap. Abidjan, Yamoussoukro cur. West African CFA franc(CFA)

Côte d'Ivoire cap. Abidjan, Yamoussoukro cur. West African CFA franc(CFA) Guinea-Bissau cap. Conakry cur. West African CFA franc(CFA)

Guinea-Bissau cap. Conakry cur. West African CFA franc(CFA) Mali cap. Bamako cur. West African CFA franc(CFA)

Mali cap. Bamako cur. West African CFA franc(CFA) Niger cap. Niamey cur. West African CFA franc(CFA)

Niger cap. Niamey cur. West African CFA franc(CFA) Senegal cap. Dakar cur. West African CFA franc(CFA)

Senegal cap. Dakar cur. West African CFA franc(CFA) Togo cap. Lomé cur. West African CFA franc(CFA)

Togo cap. Lomé cur. West African CFA franc(CFA)

Central Africa

- ECCAS (Economic Community of Central African States)

Angola(also in SADC) cap. Luanda cur. Angolan kwanza(Kz) lang. Portuguese

Angola(also in SADC) cap. Luanda cur. Angolan kwanza(Kz) lang. Portuguese Burundi (also in EAC) cap. Bujumbura cur. Burundian franc(FBu) lang. French

Burundi (also in EAC) cap. Bujumbura cur. Burundian franc(FBu) lang. French Democratic Republic of Congo (also in SADC) cap. Kinshasa cur. Congolese franc(FC) lang. Kurundi, French

Democratic Republic of Congo (also in SADC) cap. Kinshasa cur. Congolese franc(FC) lang. Kurundi, French Rwanda (also in EAC) cap. Kigali cur. Rwandan franc(RF) lang. Kinyarwanda, French, English

Rwanda (also in EAC) cap. Kigali cur. Rwandan franc(RF) lang. Kinyarwanda, French, English São Tomé and Príncipe cap. São Tomé cur. São Tomé and Príncipe dobra(Db) lang. Portuguese

São Tomé and Príncipe cap. São Tomé cur. São Tomé and Príncipe dobra(Db) lang. Portuguese

- CEMAC (Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa)

Cameroon cap. Yaoundé cur. Central African CFA franc(FCFA) lang. English, French

Cameroon cap. Yaoundé cur. Central African CFA franc(FCFA) lang. English, French Central African Republic cap. Bangui cur. Central African CFA franc(FCFA) lang. Sango,French

Central African Republic cap. Bangui cur. Central African CFA franc(FCFA) lang. Sango,French Chad cap. N'Djamena cur. Central African CFA franc(FCFA) lang. French, Arabic

Chad cap. N'Djamena cur. Central African CFA franc(FCFA) lang. French, Arabic Republic of Congo cap. Brazzaville cur. Central African CFA franc(FCFA) lang. French

Republic of Congo cap. Brazzaville cur. Central African CFA franc(FCFA) lang. French Equatorial Guinea cap. Malabo cur. Central African CFA franc(FCFA) lang. Spanish, Portuguese, French

Equatorial Guinea cap. Malabo cur. Central African CFA franc(FCFA) lang. Spanish, Portuguese, French Gabon cap. Libreville cur. Central African CFA franc(FCFA) lang. French

Gabon cap. Libreville cur. Central African CFA franc(FCFA) lang. French

East Africa

Sudan

East African Community

Burundi (also in ECCAS) cap. Bujumbura cur. Burundian franc(FBu) lang. Kirundi,French

Burundi (also in ECCAS) cap. Bujumbura cur. Burundian franc(FBu) lang. Kirundi,French Kenya cap. Nairobi cur. Kenyan shilling(KSh) lang. Swahili,English

Kenya cap. Nairobi cur. Kenyan shilling(KSh) lang. Swahili,English Rwanda (also in ECCAS) cap. Kigali cur. Rwandan franc(RF) lang. Kinyarwanda, French, English

Rwanda (also in ECCAS) cap. Kigali cur. Rwandan franc(RF) lang. Kinyarwanda, French, English Tanzania (also in SADC) cap. Dodoma cur. Tanzanian shilling(x/y) lang. Swahili,English

Tanzania (also in SADC) cap. Dodoma cur. Tanzanian shilling(x/y) lang. Swahili,English Uganda cap. Kampala cur. Ugandan shilling(USh) lang. Swahili,English

Uganda cap. Kampala cur. Ugandan shilling(USh) lang. Swahili,English

Horn of Africa

Djibouti cap. Djibouti cur. Djiboutian franc(Fdj) lang. Arabic,French

Djibouti cap. Djibouti cur. Djiboutian franc(Fdj) lang. Arabic,French Eritrea cap. Asmara cur. Eritrean nakfa(Nfk) 'lang.' Tigrinya,Arabic,Italian,English

Eritrea cap. Asmara cur. Eritrean nakfa(Nfk) 'lang.' Tigrinya,Arabic,Italian,English Ethiopia cap. Addis Ababa cur. Ethiopian birr(Br) lang. Amharic

Ethiopia cap. Addis Ababa cur. Ethiopian birr(Br) lang. Amharic Somalia cap. Mogadishu cur. Somali shilling(So)(Sh) lang. Somali,Arabic,Italian

Somalia cap. Mogadishu cur. Somali shilling(So)(Sh) lang. Somali,Arabic,Italian

Southern Africa / SADC

Angola (also in ECCAS) cap. Luanda cur. Angolan kwanza(Kz) lang. Portuguese

Angola (also in ECCAS) cap. Luanda cur. Angolan kwanza(Kz) lang. Portuguese Botswana cap. Gaborone cur. Botswana pula(P) lang. Tswana, English

Botswana cap. Gaborone cur. Botswana pula(P) lang. Tswana, English Comoros cap. Moroni cur. Comorian franc(CF) lang. Comorian, Arabic, French

Comoros cap. Moroni cur. Comorian franc(CF) lang. Comorian, Arabic, French Lesotho cap. Maseru cur. Lesotho loti(L)(M) lang. Sesotho, English

Lesotho cap. Maseru cur. Lesotho loti(L)(M) lang. Sesotho, English Madagascar cap. Antananarivo cur. Malagasy ariary (MGA) lang. Malagasy,French,English

Madagascar cap. Antananarivo cur. Malagasy ariary (MGA) lang. Malagasy,French,English Malawi cap. Lilongwe cur. Malawian kwacha(MK) lang. English

Malawi cap. Lilongwe cur. Malawian kwacha(MK) lang. English Mauritius cap. Port Louis cur. Mauritian rupee(R) lang. English

Mauritius cap. Port Louis cur. Mauritian rupee(R) lang. English Mozambique cap. Maputo cur. Mozambican metical(MTn) lang. Portuguese

Mozambique cap. Maputo cur. Mozambican metical(MTn) lang. Portuguese Namibia cap. Windhoek cur. Namibian dollar(N$) lang. Englsh

Namibia cap. Windhoek cur. Namibian dollar(N$) lang. Englsh Seychelles cap. Victoria cur. Seychellois rupee(SR)(SRe) lang. Seychellois Creole,English,French

Seychelles cap. Victoria cur. Seychellois rupee(SR)(SRe) lang. Seychellois Creole,English,French South Africa cap. Bloemfontein, Cape Town, Pretoria cur. South African rand(R) lang.11 off. lang.

South Africa cap. Bloemfontein, Cape Town, Pretoria cur. South African rand(R) lang.11 off. lang. Swaziland cap. Mbabane cur. Swazi lilangeni(L)(E) lang. SiSwati,English

Swaziland cap. Mbabane cur. Swazi lilangeni(L)(E) lang. SiSwati,English Zambia cap. Lusaka cur. Zambian kwacha(ZK) lang. English

Zambia cap. Lusaka cur. Zambian kwacha(ZK) lang. English Zimbabwe cap. Harare cur. Zimbabwean dollar($) lang. English

Zimbabwe cap. Harare cur. Zimbabwean dollar($) lang. English

See also

- Geography of Africa

- Equatorial Africa

- Black people

References

- ↑ MSU.edu

- ↑ Sub-Saharan Africa

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Arab League Online: League of Arab States

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 UNESCO - Arab States

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Centre for Marketing, Information and Advisory Services for Fishery Products in the Arab Region

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Khair El-Din Haseeb et al., The Future of the Arab Nation: Challenges and Options, 1 edition (Routledge: 1991), p.54

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Halim Barakat, The Arab World: Society, Culture, and State, (University of California Press: 1993), p.80

- ↑ John Markakis, Resource conflict in the Horn of Africa, (Sage: 1998), p.39

- ↑ Ḥagai Erlikh, The struggle over Eritrea, 1962-1978: war and revolution in the Horn of Africa, (Hoover Institution Press: 1983), p.59

- ↑ Randall Fegley, Eritrea, (Clio Press: 1995), p.xxxviii

- ↑ so e.g. Africa Works: Disorder as Political Instrument (1999, ISBN 0-85255-814-7), p. xxi: "what is usually called Black Africa — that is the former European colonies lying south of the Sahara".

- ↑ Edward Geoffrey Parrinder, African mythology, (Hamlyn: 1982), p.7

- ↑ Human skin color diversity is highest in sub-Saharan African populations http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11126724

- ↑ Claussen, Mark; Kubatzki, Claudia; Brovkin, Victor; Ganopolski, Andrey; Hoelzmann, Philipp; Pachur, Hans-Joachim (1999). "Simulation of an Abrupt Change in Saharan Vegetation in the Mid-Holocene". Geophysical Research Letters 26 (14): 2037–2040. doi:10.1029/1999GL900494

- ↑ "Sahara's Abrupt Desertification Started By Changes In Earth's Orbit, Accelerated By Atmospheric And Vegetation Feedbacks". Science Daily (Science Daily). July 12, 1999. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/1999/07/990712080500.htm

- ↑ Van Zinderen Bakker E. M. (1962-04-14). "A Late-Glacial and Post-Glacial Climatic Correlation between East Africa and Europe". Nature 194: 201–203. doi:10.1038/194201a0.

- ↑ Thompson, Lloyd A. (1989). Romans and blacks. Taylor & Francis. p. 57. ISBN 0415031850. http://books.google.com/?id=7MQOAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA57&lpg=PA57&dq=%22Sub-Saharan+Africa%22+Ethiopia+Aethiopia&q=.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Shillington, Kevin(2005). History of Africa, Rev. 2nd Ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 2, ISBN 0-333-59957-8.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Shillington, Kevin(2005). History of Africa, Rev. 2nd Ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 2-3, ISBN 0-333-59957-8.

- ↑ Shillington, Kevin(2005). History of Africa, Rev. 2nd Ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 3, ISBN 0-333-59957-8.

- ↑ Ehret, Christopher (2002). The Civilizations of Africa. Charlottesville: University of Virginia, pp. 22, ISBN 0-8139-2085-X.

- ↑ The genetic studies by Luca Cavalli-Sforza are considered pioneering in tracing the spread of modern humans from Africa.

- ↑ Sarah A. Tishkoff,* Floyd A. Reed, Françoise R. Friedlaender, Christopher Ehret, Alessia Ranciaro, Alain Froment, Jibril B. Hirbo, Agnes A. Awomoyi, Jean-Marie Bodo, Ogobara Doumbo, Muntaser Ibrahim, Abdalla T. Juma, Maritha J. Kotze, Godfrey Lema, Jason H. Moore, Holly Mortensen, Thomas B. Nyambo, Sabah A. Omar, Kweli Powell, Gideon S. Pretorius, Michael W. Smith, Mahamadou A. Thera, Charles Wambebe, James L. Weber, Scott M. Williams. The Genetic Structure and History of Africans and African Americans. Published 30 April 2009 on Science Express.

- ↑ Stearns, Peter N. (2001) The Encyclopedia of World History, Houghton Mifflin Books. p. 16. ISBN 0-395-65237-5.

- ↑ Collins, Robert O. and Burns, James. M(2007). A History of Sub-saharan Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 62, ISBN 978-0-521-86746-7

- ↑ Davidson, Basil. Africa History, Themes and Outlines, revised and expanded edition. New York: Simon and Schuster, p. 54, ISBN 0-684-82667-4.

- ↑ Shillington, Kevin(2005). History of Africa, Rev. 2nd Ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 47, ISBN 0-333-59957-8.

- ↑ McEvedy, Colin (1980) Atlas of African History, p. 44. ISBN 0-87196-480-5.

- ↑ Christopher Ehret, (2002). The Civilization of Africa. University of Virginia Press: Charlottesville, pp. 93 ISBN 0-8139-2085-X.

- ↑ Fox, C.L., 'mtDNA analysis in ancient Nubians supports the existence of gene flow between Sub-Sahara and North Africa in the Nile Valley', in Annals of Human Biology, 24, 3, 217–227. (abstract).

- ↑ AncientSudan.org

- ↑ Mokhtar (editor), AnciGent Civilizations of Africa Vo. II, General History of Africa, UNESCO, 1990

- ↑ Oman in history By Peter Vine Page 324

- ↑ Shaping of Somali society Lee Cassanelli pg.92

- ↑ Futuh Al Habash Shibab ad Din

- ↑ Sudan Notes and Records – Page 147

- ↑ African Archaeological Review, Volume 15, Number 3, September 1998 , pp. 199-218(20)

- ↑ Davidson, Basil. Africa History, Themes and Outlines, revised and expanded edition. New York: Simon and Schuster, pp. 87-107, ISBN 0-684-82667-4.

- ↑ Wesler,Kit W.(1998). Historical archaeology in Nigeria. Africa World Press pp.143,144 ISBN ISBN 0-86543-610-X, 9780865436107.

- ↑ Pearce, Fred. African Queen. New Scientist, 11 September 1999, Issue 2203.

- ↑ The Slave Trade

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Shillington, Kevin(2005). History of Africa, Rev. 2nd Ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 138,139,142, ISBN 0-333-59957-8.

- ↑ M. Martin, Phyllis and O'Meara, Patrick (1995). Africa 3rd edition, Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, p. 156, ISBN 0-253-32916-7.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 "Africa's Malaria Death Toll Still "Outrageously High", Afshin Molavi, National Geographic News, June 12, 2003.

- ↑ ddp-ext.worldbank.org/ext/ddpreports

- ↑ World Population Prospects: The 2006 Revision Population Database

- ↑ According to the CIA Factbook: Angola, Benin, Burundi, Burkina Faso, the Central African Republic, Cameroon, Chad, the Republic of Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, the Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, and Zambia

- ↑ Goal: Reduce child mortality, Unicef, retrieved February 24, 2009.

- ↑ Goal 4: Reduce Child Mortality, worldbank.org, retrieved 7-8-2009

- ↑ Independent.co.ug

- ↑ InsideSomalia.org

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 (2009). Africa Development Indicators 2008/2009: From the World Bank Africa Database AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT INDICATORS. World Bank Publications, p. 28, ISBN 0-8213-7787-6, 9780821377871.

- ↑ Transparency International. Corruption Perception Index(CPI) 2009.

- ↑ World Bank. Doing Business 2010, Economy Ranking

- ↑ Creamer Media. Africa’s energy problems threatens growth, says Nepad CEO 12 November 2009

- ↑ CreamerMedia.co.za

- ↑ CreamerMedia.co.za

- ↑ RedOrbit.com Redorbit

- ↑ Flatow, Ira. Could Africa Leapfrog The U.S. In Solar Power?. Science Friday 6 June 2008.

- ↑ Hepeng, Jia. China to train developing nations in solar technologies. SciDevNet 20 August 2004.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 English, Cynthia. Radio the Chief Medium for News in Sub-Saharan Africa. Gallup 23 June 2008.

- ↑ Africa Calling: Cellphone usage sees record rise. Mail&Guardian: 23 October 2009.

- ↑ Aker, Jenny C.(2008). “Can You Hear Me Now?”How Cell Phones are Transforming Markets in Sub-Saharan Africa, Center for Global Development.

- ↑ MG.co.za

- ↑ Pfanner, Eric. Competition increases for pay TV in sub-Saharan Africa. New York Times 6 August 2007.

- ↑ Ken Gwilliam, Vivien Foster, Rodrigo Archondo-Callao, Cecilia Briceño-Garmendia, Alberto Nogales, and Kavita Sethi(2008). Africa infrastructure country diagnostic, Roads in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank and the SSATP: p. 4

- ↑ USGS.gov

- ↑ USGS.gov

- ↑ Gold-Eagle.com

- ↑ USGS.gov

- ↑ USGS.gov

- ↑ pp 2-3 Bepress.com

- ↑ MBendi.com

- ↑ World-Nuclear.org

- ↑ Ghazvinian, John (2008). Untapped: The Scramble for Africa's Oil. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, pp. 1-16, ISBN 0-15-603372-0, 9780156033725.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Christopher Ehret, (2002). The Civilization of Africa. University of Virginia Press: Charlottesville, pp. 98 ISBN 0-8139-2085-X.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Vandaveer, Chelsie(2006). What was the cotton of Kush? KillerPlants.com, Plants That Change History Archive.

- ↑ National Research Council (U.S.). Board on Science and Technology for International Development (1996). Lost Crops of Africa: Grains. National Academy Press, ISBN 0-309-04990-3, 9780309049900.

- ↑ WorldDefenseReview.com

- ↑ Business24-7.ae

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 81.2 Bowden, Rob (2007). Africa South of the Sahara. Coughlan Publishing: p. 37, ISBN 1-4034-9910-1.

- ↑ Blogspot.com

- ↑ Mathiason, Nick (2009-11-02). "Global protocol could limit Sub-Saharan land grab". The Guardian (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2009/nov/02/global-protocol-subsahara-land-grab. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Gabara, Nthambeleni. Developed Nations Should Invest In African Universities. Buanews, 12 November 2009

- ↑ Nordling, Linda. Africa Analysis: Progress on science spending?. ScidevNet, 29 October 2009.

- ↑ South Africa’s Investment in Research and Development on the Rise. Department of Science and Technology: Science and Technology, 22 June 2006.

- ↑ "User fees for health: a background". http://www.eldis.org/healthsystems/userfees/background.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-28.

- ↑ "Implementation of the Bamako Initiative: strategies in Benin and Guinea". http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=10173105&dopt=Abstract. Retrieved 2006-12-28.

- ↑ "Manageable Bamako Initiative schemes". http://www.medicusmundi.ch/mms/services/bulletin/bulletin200201/kap01/07kuechler.html. Retrieved 2006-12-28.

- ↑ Xinhua - English

- ↑ Brown, Keith and Ogilvie, Sarah(2008). Concise encyclopedia of languages of the world Concise Encyclopedias of Language and Linguistics Series. Elsevier, p. 12, ISBN 0-08-087774-5, 9780080877747.

- ↑ Peek, Philip M. and Yankah, Kwesi(2004). African folklore: an encyclopedia. London:(Rourledge)Taylor & Francis, p. 205, ISBN 0-415-93933-X, 9780415939331

- ↑ Schneider, Edgar Werner and Kortmann, Bernd(2004). A handbook of varieties of English: a multimedia reference tool, Volume 1. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 867-868, ISBN 3-11-017532-0, 9783110175325.

- ↑ Corballis, Michael C.(2003). From hand to mouth: the origins of language. Princeton University Press, p. 130, ISBN 0-691-11673-3, 9780691116730.

- ↑ Güldemann, Tom and Edward D. Elderkin (forthcoming) "On external genealogical relationships of the Khoe family". In Brenzinger, Matthias and Christa König (eds.), Khoisan languages and linguistics: the Riezlern symposium 2003. Quellen zur Khoisan-Forschung 17. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe.

- ↑ Bellwood, Peter S.(2005). First farmers: the origins of agricultural societies. Wiley-Blackwell, p. 218, ISBN 0-631-20566-7, 9780631205661.

- ↑ Prof. James Giblin, Department of History, The University of Iowa. Issues in African History

- ↑ Shillington, Kevin(2005). History of Africa, Rev. 2nd Ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 295, ISBN 0-333-59957-8.

- ↑ Christopher Ehret, (2002). The Civilizations of Africa. Charlottesville: University of Virginia, p. 7-8, ISBN 0-8139-2085-X.

- ↑ Hellbrunn Timeline of Art. African Influences in Modern Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 The Middle East, nos. 135-145, (IC Publications ltd.: 1985), p.13

- ↑ Books.Google.com Lloyd E. Hudman, Richard H Jackson, Geography of Travel & Tourism, 4 edition, (Delmar Cengage Learning: 2002), p.383

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 CIA - The World Factbook -- Sudan

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 Anne K. Bang, Sufis and scholars of the sea: family networks in East Africa, 1860-1925, (Routledge: 2003), p.114

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 Bulletin on Islam and Christian-Muslim relations in Africa, Volumes 2-4, (Centre for the Study of Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations, Selly Oak Colleges, 1984)

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 Larousse (Firm), The Kingfisher young people's atlas of the world, (Scholastic, Inc., 1998), p.64.

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 Catharine Cookson, Encyclopedia of religious freedom, (Taylor & Francis: 2003), p.1.

- ↑ Baldick, Julian (1997). Black God: the Afroasiatic roots of the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim religions. Syracuse University Press:ISBN 0815605226

- ↑ Christopher Ehret, (2002). The Civilizations of Africa. Charlottesville: University of Virginia, pp. 102-103, ISBN 0-8139-2085-X.,

- ↑ Davidson, Basil(1969). The African Genius,An Introduction to African Social and Cultural History. Little Brown and Company: Boston, pp. 168-180. Library of Congress 70-80751.

- ↑ Eglash, Ron: "African Fractals: Modern computing and indigenous design.” Rutgers 1999 ISBN 0-8135-2613-2

- ↑ Christopher Ehret, (2002). The Civilizations of Africa. Charlottesville: University of Virginia, p. 103, ISBN 0-8139-2085-X.

- ↑ ScienceDaily.com

- ↑ "'Oldest' prehistoric art unearthed". BBC News. 2002-01-10. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/1753326.stm. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- ↑ Rock Art In Africa, Trust for African Rock Art (TARA)

- ↑ African Influences in Modern Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ↑ Alexandre, Marc(1998). World Bank Publication: DC. ISBN 0-8213-4195-2, 9780821341957

- ↑ Yoshida, Reiko. Proclamation 2005: Barcloth making in Uganda Unesco: Intangible Cultural Heritage (Uganda) 13 May 2009

- ↑ About.com

- ↑ AllAfrica.com

- ↑ "European Soccer's Racism Problem". Deutsche Welle (Deutsche Welle). December 2, 2005. http://www.dw-world.de/dw/article/0,2144,1798795,00.html

- ↑ Bicourt, John. John Bicourt: Do Kenyan and Ethiopian runners have a genetic advantage? Inside the Games,Tuesday, 28 April 2009.

- ↑ Tucker, Ross and Dugas, Jonathan. Sport's great rivalries: Kenya vs. Ethiopia, and a one-sided battle (at least on the track), The Science of Sport, 14 July 2008.

- ↑ Malik, Nesrine (2009-11-23). "'Nubian monkey' song and Arab racism". The Guardian (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2009/nov/23/nubian-monkey-arab-racism. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- ↑ Al-Shalachi, Hadeel(2009-11-19).Haifa Wehbe: Controversy Over 'Nubian Monkey' Song. www.huffingtonpost.com, retrieved 19-04-2010.

- ↑ Towson.edu

- ↑ Worldbank.org

- ↑ CDCdevelopmentSolutions.org

- ↑ USaid.gov

- ↑ Transparency.org

Sources

- Taking Action to Reduce Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa, World Bank Publications (1997), ISBN 0-8213-3698-3.

Bibliography

- Petringa, Maria: Brazza, A Life for Africa. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2006. ISBN 978-1-4259-1198-0

- Wm. Roger Louis and Jean Stengers: E.D. Morel's History of the Congo Reform Movement, Clarendon Press Oxford, 1968.

External links

- Mo Ibrahim Index(governance index), Mo Ibrahim Foundation

- 50 Factoids about Sub-Saharan Africa

- The Story of Africa - BBC World Service

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||